Op-Ed: Kevin Schmidt: How vague statutory language enabled the Biden administration’s CHIPS Act overreach, and what Congress must do next

When Congress rejected sweeping child care subsidies in the Inflation Reduction Act, the Biden administration’s Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo reportedly told her staff, “if Congress wasn’t going to do what they should have done, we’re going to do it in implementation.”

That wasn’t just rhetoric — it became a blueprint for how the Biden administration would abuse a bill meant to support the domestic production of semiconductors, the CHIPS and Science Act, to instead impose progressive social policies through administrative fiat.

After more than two years of government stonewalling in Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) litigation, the Americans for Prosperity Foundation uncovered how the Biden administration’s Department of Commerce made political decisions to burden domestic chip manufacturers with additional requirements and mandates beyond what the statute allowed, undermining the national security argument that was key the bill’s passage.

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision in Loper Bright v. Raimondo, Congress has a renewed opportunity — and responsibility — to reclaim its legislative authority instead of granting vague authority to federal agencies like the language in the CHIPS Act.

The documents we obtained reveal the Biden administration’s strategy to circumvent congressional intent by embedding social policy into industrial legislation implementation. These included child care mandates, profit-sharing requirements, and prohibitions on stock buybacks. These requirements were not included in the statutory text of the CHIPS Act. In fact, Congress debated and rejected some of them during the legislative process. Yet the Commerce Department imposed them anyway, citing broadly worded statutory language as justification.

Raimondo knew they exceeded the statute’s bounds, which is why she preemptively asked her staff to come up with “a short list of issues related to CHIPS where we’ve made decisions that have political ramifications” (emphasis added).

Another email obtained in litigation revealed how Raimondo advisors outlined the various “Administrative requirements” and “Administrative Preferences” that were not included in the “Statutory Requirements.”

This episode illustrates a deeper structural problem: Congress’s habit of writing vague, aspirational laws that delegate too much discretion to federal agencies. When statutes are filled with platitudes and open-ended goals, they invite executive overreach.

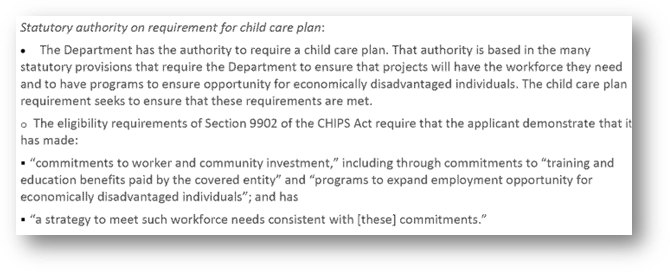

For example, the CHIPS Act didn’t mandate child care or profit-sharing. But it did give the Department of Commerce broad authority to set “criteria” for federal support. A senior advisor to Raimondo argued the CHIPS Act’s vague reference to “workforce needs” justified requiring child care plans.

Similarly, the advisor used ellipses to strip statutory context and justify a profit-sharing scheme — dubbed “Upside Sharing” — based on unrelated language about application fees. The memo also argued it could add a profit-sharing requirement because the statute said the department was tasked with “‘determin[ing] the appropriate amount’ of funding for each project.”

Staff for key Republican senators who helped draft and negotiate the bill were perplexed by the inclusion of upside sharing according to call notes with the CHIPS program staff: "What is the legal authority for upside sharing. This was voted down in the [Sen. Warren] amendment. It was not something that they had drafted or negotiated."

Fortunately, Congress is beginning to recognize the dangers of vague delegation. The Senate’s Post-Chevron Working Group, led by Sen. Eric Schmitt (R., Mo.) released a powerful new tool: the “Legislative Drafter’s Guide to Deference, Delegation, and Discretion.” This guide offers concrete recommendations for how Congress can write laws that:

Limit agency discretion by assigning only ministerial duties

Avoid vague buzzwords that invite interpretation

Embed cost-benefit analysis directly into statutory text

Hold elected officials—not bureaucrats—accountable for policy decisions

As the guide puts it: “The best way to stop administrative deference, delegation, and discretion is to give agencies nothing more than ministerial duties.”

This legislative momentum was on full display at a late July Senate Hearing titled, “The Future is Loper Bright: Congress’s Role in the Regulatory Landscape.” Subcommittee Chairman Sen. James Lankford’s (R., Okla.) hearing featured testimony from legal scholars and former lawmakers who emphasized the urgent need for Congress to reclaim its constitutional legislative authority after Loper Bright.

One of the witnesses, Professor Chad Squitieri of Catholic University, argued that Congress “should make more policy decisions itself, rather than delegate substantial discretion to agencies.”

This hearing marks a pivotal moment in the post-Chevron era. It signals that Congress is beginning to take seriously its responsibility to write laws that are not only enforceable, but also resistant to executive reinterpretation.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Loper Bright, where Raimondo was the named defendant, wasn’t just a legal turning point: it was a rebuke of the kind of agency behavior Raimondo herself exemplified when she used the CHIPS Act to advance policies Congress had explicitly rejected.

When Congress writes vague laws, it cedes power to the executive branch. If lawmakers want to reclaim their constitutional role, and prevent future abuses like those uncovered in the CHIPS Act, they must start with better legislative drafting.

The post-Chevron guide shows the way. The July 30 hearing shows there’s momentum. Now it’s up to Congress to follow through.

Kevin Schmidt is director of investigations at Americans for Prosperity Foundation